By GINA KOLATA

My son, Stefan, was running in a half marathon in Philadelphia last month when he heard someone coming up behind him, breathing hard.

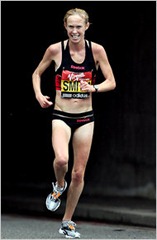

To his surprise, it was an elite runner, Kim Smith, a blond waif from New Zealand. She has broken her country’s records in shorter distances and now she’s running half marathons. She ran the London marathon last spring and will run the New York marathon next month.

That day, Ms. Smith seemed to be struggling. Her breathing was labored and she had saliva all over her face. But somehow she kept up, finishing just behind Stefan and coming in fifth with a time of 1:08:39.

And that is one of the secrets of elite athletes, said Mary Wittenberg, president and chief executive of the New York Road Runners, the group that puts on the ING New York City Marathon. They can keep going at a level of effort that seems impossible to maintain.

“Mental tenacity — and the ability to manage and even thrive on and push through pain — is a key segregator between the mortals and immortals in running,” Ms. Wittenberg said.

You can see it in the saliva-coated faces of the top runners in the New York marathon, Ms. Wittenberg added.

“We have towels at marathon finish to wipe away the spit on the winners’ faces,” she said. “Our creative team sometimes has to airbrush it off race photos that we want to use for ad campaigns.”

Tom Fleming, who coaches Stefan and me, agrees. A two-time winner of the New York marathon and a distance runner who was ranked fourth in the world, he says there’s a reason he was so fast.

“I was given a body that could train every single day.” Tom said, “and a mind, a mentality, that believed that if I trained every day — and I could train every day — I’ll beat you.”

“The mentality was I will do whatever it takes to win,” he added. “I was totally willing to have the worst pain. I was totally willing to do whatever it takes to win the race.”

But the question is, how do they do it? Can you train yourself to run, cycle, swim or do another sport at the edge of your body’s limits, or is that something that a few are born with, part of what makes them elites?

Sports doctors who have looked into the question say that, at the very least, most people could do a lot better if they knew what it took to do their best.

“Absolutely,” said Dr. Jeroen Swart, a sports medicine physician, exercise physiologist and champion cross-country mountain biker who works at the Sports Science Institute of South Africa.

“Some think elite athletes have an easy time of it,” Dr. Swart said in a telephone interview. Nothing could be further from the truth.

And as athletes improve — getting faster and beating their own records — “it never gets any easier,” Dr. Swart said. “You hurt just as much.”

But, he added, “Knowing how to accept that allows people to improve their performance.”

One trick is to try a course before racing it. In one study, Dr. Swart told trained cyclists to ride as hard as they could over a 40-kilometer course. The more familiar they got with the course, the faster they rode, even though — to their minds — it felt as if they were putting out maximal effort on every attempt.

Then Dr. Swart and his colleagues asked the cyclists to ride the course with all-out effort, but withheld information about how far they’d gone and how far they had to go. Subconsciously, the cyclists held back the most in this attempt, leaving some energy in reserve.

That is why elite runners will examine a course, running it before they race it. That is why Lance Armstrong trained for the grueling Tour de France stage on l’Alpe d’Huez by riding up the mountain over and over again.

“You are learning exactly how to pace yourself,” Dr. Swart said.

Another performance trick during competitions is association, the act of concentrating intensely on the very act of running or cycling, or whatever your sport is, said John S. Raglin, a sports psychologist at Indiana University.

In studies of college runners, he found that less accomplished athletes tended to dissociate, to think of something other than their running to distract themselves.

“Sometimes dissociation allows runners to speed up, because they are not attending to their pain and effort,” he said. “But what often happens is they hit a sort of physiological wall that forces them to slow down, so they end up racing inefficiently in a sort of oscillating pace.” But association, Dr. Raglin says, is difficult, which may be why most don’t do it.

Dr. Swart says he sees that in cycling, too.

“Our hypothesis is that elite athletes are able to motivate themselves continuously and are able to run the gantlet between pushing too hard — and failing to finish — and underperforming,” Dr. Swart said.

To find this motivation, the athletes must resist the feeling that they are too tired and have to slow down, he added. Instead, they have to concentrate on increasing the intensity of their effort. That, Dr. Swart said, takes “mental strength,” but “allows them to perform close to their maximal ability.”

Dr. Swart said he did this himself, but it took experience and practice to get it right. There were many races, he said, when “I pushed myself beyond my abilities and had to withdraw, as I was completely exhausted.”

Finally, with more experience, Dr. Swart became South Africa’s cross-country mountain biking champion in 2002.

Some people focus by going into a trancelike state, blocking out distractions. Others, like Dr. Swart, have a different method: He knows what he is capable of and which competitors he can beat, and keeps them in his sight, not allowing himself to fall back.

“I just hate to lose,” Dr. Swart said. “I would tell myself I was the best, and then have to prove it.”

Kim Smith has a similar strategy.

“I don’t want to let the other girls get too far ahead of me,” she said in a telephone interview. “I pretty much try and focus really hard on the person in front of me.”

And while she tied her success to having “some sort of talent toward running,” Ms. Smith added that there were “a lot of people out there who were probably just as talented. You have to be talented, and you have to have the ability to push yourself through pain.”

And, yes, she does get saliva all over her face.

“It’s not a pretty sport,” Ms. Smith said. “You are not looking good at the end.”

As for the race she ran with my son, she said: “I’m sorry if I spit all over Stefan.” (She didn’t, Stefan said.)

Reprinted from The New York Times

Is "winning" really that important that athletes at every level are all too readily willing to make a deal with the devil and sell their priceless good name, character and integrity for the worthless thrill of an ultimately meaningless victory?

Is "winning" really that important that athletes at every level are all too readily willing to make a deal with the devil and sell their priceless good name, character and integrity for the worthless thrill of an ultimately meaningless victory?

A friend of mine does not make New Year’s Resolutions. “Studies say that most New Year’s Resolutions are broken after a few weeks,” she told me. “So, instead, I make New Year’s Goals.”

A friend of mine does not make New Year’s Resolutions. “Studies say that most New Year’s Resolutions are broken after a few weeks,” she told me. “So, instead, I make New Year’s Goals.”